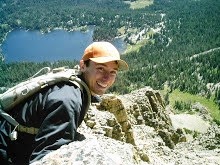

I feel like I write too much about education, but on the other hand, I'd rather write about education than my other areas of interest. All the world needs is one more sports blogger. I'm not about to post up pages and pages of statistics and shock jock opinions about what happened in the Toronto-New Jersey basketball game last night. Every once and a while I will see the need to roast somebody, but that time is not right now. Similarly worthless is a political blog. Aren't there enough Hannitys and Coulters and Frankens and Limbaughs to make the world vomit already? Nobody should have to read that stuff when it's already filling the airwaves TV listings. But just like sports, every once and a while I'll see something that I feel inclined to write about. Another subject I could write about is my own life. I'm sure everyone who reads my blog would love to see pictures of me at ESPN's gameday when they came to Provo, Courtney and I going camping and our cat Spock donning the Cone of Shame following her declawing and spaying. As much as I'm sure about that, I'm not that sure of that, so I don't post it. (Not here, at least. I post albums on facebook, and I don't like doing it twice unless it's something really entertaining or important).

I feel like I write too much about education, but on the other hand, I'd rather write about education than my other areas of interest. All the world needs is one more sports blogger. I'm not about to post up pages and pages of statistics and shock jock opinions about what happened in the Toronto-New Jersey basketball game last night. Every once and a while I will see the need to roast somebody, but that time is not right now. Similarly worthless is a political blog. Aren't there enough Hannitys and Coulters and Frankens and Limbaughs to make the world vomit already? Nobody should have to read that stuff when it's already filling the airwaves TV listings. But just like sports, every once and a while I'll see something that I feel inclined to write about. Another subject I could write about is my own life. I'm sure everyone who reads my blog would love to see pictures of me at ESPN's gameday when they came to Provo, Courtney and I going camping and our cat Spock donning the Cone of Shame following her declawing and spaying. As much as I'm sure about that, I'm not that sure of that, so I don't post it. (Not here, at least. I post albums on facebook, and I don't like doing it twice unless it's something really entertaining or important).To be honest, what I write directly correlates with what I read (although correlation does not infer causation; I read a whole lot more than I write about, and you ought to be glad, what with all the comparative politics studies and adolescent development crap I've read this semester). Two weeks ago I picked up a great book from the

Jerome library book sale for $1. It is titled 'The Moral Dimensions of Teaching," and caught my interest because the teacher education program at BYU teaches the importance of the moral dimensions of teaching. A few years ago this agency was going to deny accreditation to BYU''s teacher education program because they did not teach the moral dimensions of teaching as addressed by John Goodlad (the editor of this book). In a couple of months they scrounged together a plan that incorporated Goodlad's ideas and started educating future teachers in its ways. The result is S.A.N.E., BYU's version of Goodlad's teachings. S.A.N.E. stands for Stewardship, Access to knowledge, Nurturing Pedagogy, and Enculturating democracy. I was first taught this in my teaching class earlier this semester, but it came up on the first day of my second block teaching course (adolescent development). From then I could tell that it's pretty important, which is why I bought the book.

Jerome library book sale for $1. It is titled 'The Moral Dimensions of Teaching," and caught my interest because the teacher education program at BYU teaches the importance of the moral dimensions of teaching. A few years ago this agency was going to deny accreditation to BYU''s teacher education program because they did not teach the moral dimensions of teaching as addressed by John Goodlad (the editor of this book). In a couple of months they scrounged together a plan that incorporated Goodlad's ideas and started educating future teachers in its ways. The result is S.A.N.E., BYU's version of Goodlad's teachings. S.A.N.E. stands for Stewardship, Access to knowledge, Nurturing Pedagogy, and Enculturating democracy. I was first taught this in my teaching class earlier this semester, but it came up on the first day of my second block teaching course (adolescent development). From then I could tell that it's pretty important, which is why I bought the book.The book is a collection of chapters written by Goodlad and some of his buddies. I finished the first one earlier this week, written by Goodlad, titled 'The Occupation of Teaching in Schools.' The focus of this chapter is to describe teacher education and to identify the disconnect between teaching in the classroom, policymaking in the boardroom, and administrating in the Principal's office. At the end, he introduces the moral dimensions of teaching as necessary to describe the mission of teaching, and thus create a uniform basis of training teachers across the country.

The problem all began when a famous historian was hired by Harvard for an exorbitant salary, and he was allowed to not teach his first year at the university. From that point on universities became houses of research first, and education second. "By the 1980s," Goodlad wrote, "professors in these schools, if involved with future teachers at all, were more likely to be studying them than preparing them to teach." The conditions were rocky in the teacher-administrator relationship at this point, too. Before my great-grandpa Vern died in 1990, my father visited him on his deathbed. Coach recalls this about their conversation:

"Grandpa Vern asked how teaching was going and I said fine. He responded with, 'Be sure to keep those damned administrators out of your classroom.'" The preparation for administrators in schools focused more on management techniques and less on education. However little the principal actually knew about education, it was generally assumed from the outside that they have authority in regard to the evaluation of teachers, when in fact, they knew very little about what goes on (or is supposed to go on) in a classroom. These administrators are the ones that go on to write the policy that outlines what should happen in the classroom. Luckily this is in most cases, not the situation of today. Most schools offering a masters of educational administration require at least three years of teaching, making for more prepared administrators founded in principles of teaching and education.

"Grandpa Vern asked how teaching was going and I said fine. He responded with, 'Be sure to keep those damned administrators out of your classroom.'" The preparation for administrators in schools focused more on management techniques and less on education. However little the principal actually knew about education, it was generally assumed from the outside that they have authority in regard to the evaluation of teachers, when in fact, they knew very little about what goes on (or is supposed to go on) in a classroom. These administrators are the ones that go on to write the policy that outlines what should happen in the classroom. Luckily this is in most cases, not the situation of today. Most schools offering a masters of educational administration require at least three years of teaching, making for more prepared administrators founded in principles of teaching and education.Goodlad mentions the appeal of teaching as a calling. He brings up examples of future teachers he interviewed who recalled disappointed parents, teachers trying to talk them out of it, and friends who think they're crazy. Many, however, described teaching as "exceedingly important and potentially satisfying--as a calling." According to Goodlad those who take upon themselves this calling--where good judgment and exceptional skill is involved in order to be effecient--must abide by a set of normative principles he calls the moral dimensions of teaching.

Enculturation: Educators must provide their students with "critical perspectives on the nature of democratic societies." As a poli sci nut, I couldn't agree more. This is necessary for the "induction of the young into our culture."

Access to Knowledge: Every young person deserves an equal shot at being educated. As much as many Americans believe this is actually carried out by our great nation, it is not, and to them I refer Jonothan Kozol's Shame of a Nation or Savage Inequalities. "Opportunities to gain access to the most generally useful knowledge are maldistributed in most schools, with poor and minority children and youths on the short end of the distribution." How could this be the case? "Casual, misguided, decisions with regard to grouping and tracking students, apportioning the domains of knowledge and knowing in the curriculum, allocating daily and weekly instructional time, scheduling, and other practices often distribute access to knowledge unfairly and inequitably." Teachers carry the responsibility of recognizing programs that do this within the school and standing up for the fair and equitable distribution of access to knowledge.

The Teacher and the Taught: Teachers must realize that their students are in a compulsory setting and that they did not choose to be there. Anything we can do as teachers to bring the subjects we teach into the students' realm of importance will give them more motivation to succeed. Students are only motivated in the core subjects (English, mathematics, social studies and sciences) when they aspire to more schooling. Teachers must be focused on making the subject matter important for the individual.

The Teacher and the Taught: Teachers must realize that their students are in a compulsory setting and that they did not choose to be there. Anything we can do as teachers to bring the subjects we teach into the students' realm of importance will give them more motivation to succeed. Students are only motivated in the core subjects (English, mathematics, social studies and sciences) when they aspire to more schooling. Teachers must be focused on making the subject matter important for the individual.Renewing School Settings: There is an overwhelming trend in the nation calling for reform in schools and requiring results. When positive results of one reform aren't seen immediately, another reform is enacted to "fix the problem." Goodlad says, "If schools are to become the responsive, renewing institutions that they must, the teachers in them must be purposefully engaged in the renewal process...'School renewal' becomes a nonevent, one more in the cycle of nonevents that characterize the school improvement enterprise.

More teacher involvement in the reform/renewal process requires more time. "Teachers employed for 180 days and required to teach 180 days simply will not renew their schools. It is ludicrous and self-deceiving to believe that they will. Further, such an expectation borders on the immoral. The answer...is 180 days of teaching and 20 or more additional days of institutional renewal. We can begin to look seriously at teaching as a profession when it no longer is a part-time job. Teaching will become a full-time occupation when the public sees the need for it." Nationwide reforms will not provide all the answers for every single school because the contextual factors for every school are different. It is up to the teachers to provide insight into how the school should adjust to best meet the needs of the school's unique conglomeration of students--not some suit in DC. Any teacher could tell you this is true, yet, like Goodlad said, to ask teachers to effectively do this in the amount of time their given every year is more than slightly ridiculous.

The opening chapter provided an excellent hook for me, and I hope the rest of the book is as good as this.